Semantic Satiation(语义饱和)——一个词越看越不认识;因熟视,而无睹

不断看到一个词,突然觉得不认识了……

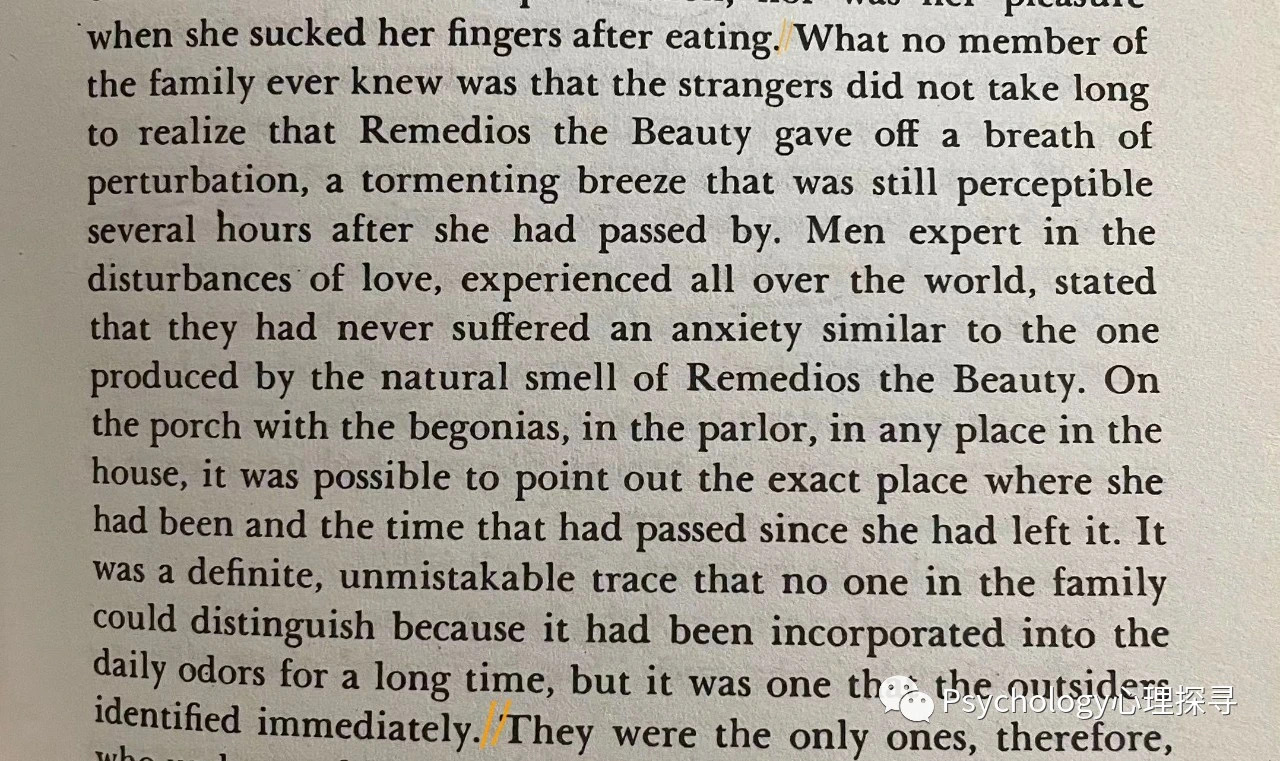

经常闻到某种气味,以至于感觉不到了……

快速火爆的歌曲往往也很快被遗忘……

不断翻看书中同一段话,越看越“看不进去”……

家长不断对小孩重复讲某句话或某个词,小孩越来越置若罔闻……

空洞的官话套话从你左耳进右耳出激荡不起任何涟漪……

你还有其他什么类似经历?

Tell me if you’ve ever been in this situation before. You have to repeat a word over and over again, saying the word until it loses meaning. You start to question whether or not that word is even the right word. Are you saying it right? Is it spelled right? Does it actually mean anything?

告诉我这一场景是否似曾相识。你需要不断重复一个词,直到你发现这个词失去了它的意思。你开始怀疑这个词到底正不正确。你是否说对了?是否拼对了?是否真的有什么含义?

This might happen with the simplest words: stop, play, night. Once you get your mind off of the word for a few minutes, you automatically remember its meaning and spelling as if nothing happened.

这可能发生于一些最简单的词:Stop、Play、Night。但一旦你停止想这个词几分钟,一切就又恢复正常。

This psychological phenomenon is called semantic satiation.

这种心理现象被称为语义饱和。

While this may have felt like a sort of cognitive processing glitch, some scientists, such as cognitive neuroscientist David Huber from the University of Massachusetts, believe this experience gives us an important insight into how our minds perceive the external world.

尽管这感觉起来可能像是我们认知处理机能出了点儿小障碍,一些科学家,比如马萨诸塞州大学认知神经科学家 David Huber 认为,这一体验能够让我们深入洞察到我们的大脑是如何认知外部世界的。

Psychologists have been aware of this bizarre effect since way back in 1907, when it was first described by The American Journal of Psychology. However, it took until the 1960’s before someone decided to study it seriously. Leon James, a professor of psychology at the University of Hawaii, made it the subject of his doctoral thesis, coining the term semantic satiation.

自1907年,美国心理学杂志描述了这一现象后,这一现象就开始广为心理学家所知。但直到上世纪60年代,才有人决定认真研究这一现象。夏威夷大学心理学教授 Leon James将其作为了其博士论文主题,并制造了这个词:语义饱和。

Dissociation Station

前方到站:解离

Put simply, sensory signals trigger the firing of regions in the brain that are linked to concepts and categories that give those signals meaning. The sound of a word is one such signal. After firing once it takes more energy to fire those brain cells a second time. So when we hear a word the second time around, it is more energy intensive for the brain to continually link it to the concepts associated with the word. It takes even more energy a third time. A fourth time, and maybe those cells won’t even fire. James called this reactive inhibition.

简而言之,感官信号会触发大脑中与概念和分类相关、赋予这些信号意义的区域放电。一个词的读音就是这类信号之一。在放电一次后,会需要这些脑细胞耗费更多能量再次放电。所以,当我们第二次听到某个词时,大脑需要耗费更多能量去为这个词匹配其概念。第三次则会耗费更多能量。到了第四次,可能这些细胞甚至就罢工了(大脑为了节省能量)。James将其称为“反应抑制”。

The more you are exposed to a set of stimuli, the more resilient to the stimuli you become. This phenomenon is illustrated in what is a now famous study: Researchers played a loud tone to a sleeping cat, and the cat was up and alert immediately. The researchers continued to play the loud tone once the cat had fallen asleep, again and again, and each time the cat’s reaction was a little more subdued, until it eventually hardly reacted at all. But when the researchers altered the tone, only slightly, the cat reacted like it was hearing it for the first time again.

你接触一系列刺激物的次数越多,你就变得越不容易受影响。这一现象在当今知名的研究中也得到了说明:研究人员对一只在睡眠状态的猫播放一个很响的声音,这只猫立即惊醒。在猫又睡着后,研究人员继续重复播放这一声音,随着每一次播放,猫的反应程度逐渐降低,直至毫无反应。但当研究人员更改了这一声音后,虽然只是稍微更改,这只猫做出的反应就像是第一次听到这一声音一样。

For humans, no word is immune from semantic satiation, but it may take longer for different words to lose their meaning depending on the emotional strength of your concepts of said word. For example, you may have more potent imagery tied to a word like "hospital" compared to a word like "lamp." Because of your previous experiences in hospitals, and the associated connotations of the word, your mind cycles through meaningful categories that are linked to the word hospital, making it harder to reach a point of detachment. Whereas the word lamp has less meaningful implications. (That is, unless you have had a traumatic lamp-related incident.) The dissociative effects of semantic satiation have also been studied in the treatment of phobias and speech anxiety.

对人类来说,没有词汇是对这种语义饱和现象免疫的,但不同的词可能需要更长时间才会让人感觉其失去含义,这取决于你对具体词汇的相应概念的情感强度。例如,相对于台灯来说,你可能对诸如医院这个词有着更强烈的画面联系。因为你之前在医院的经历,与这个词相关联的内涵含义,你的大脑会搜索与医院这个词相关联的所有富有意义的分类,让其较难脱离其含义。但与台灯这个词相关联的含义则较少(除非你曾经历过某件具有创伤性的与台灯相关的事件)。语义饱和的这种解离现象在恐惧症和演讲焦虑的治疗方法中也得到了研究。

Certain therapies, for example, use repetition as a way to expose patients to their worst fears. Eventually, those fears become normalized. Facing the same concept, word, or event again and again may take away its meaning, and therefore, its power.

比如,特定疗法中使用“重复”来将患者暴露于他们的最深恐惧。最终,这些恐惧会变得正常化。重复面对同样的概念、词汇或事件会剥离其含义,从而剥离其力量。

Semantic sanitation should be considered in much larger questions of psychology about repetition, working memory, and how the brain interacts with different stimuli. If it can be used to tackle problems like stutters or fears, who knows what else it can do for the mind!

语义饱和应该被放在一些更大的心理学问题中被考虑,比如重复、工作记忆以及大脑如何与不同刺激物互动等。如果它可以被用于应对比如结巴或恐惧等问题,谁知道它对大脑还有其他什么不为所知的潜力!

Been There, Done That

因熟视,而无睹

Huber has been investigating semantic satiation, or what is now known more generally in academic circles as associative satiation, for a few years now. He thinks there is something similar going on when words lose meaning through repetition and when our brains disregard freshly-processed information about our environment.

Huber 如今已经研究语义饱和现象数年之久,这一术语在学术圈更多被称为关联饱和。他认为词汇在被重复后会失去含义,这和我们的大脑忽视对周围环境的最新处理信息存在一定共同点。

Neural habituation, a process studied by Huber, is the reduction of our cognitive processing capacities in relation to things we have already experienced. From a neurological point of view, we don’t need to waste valuable resources interpreting information from our senses when it's already been processed before. Habituation helps our brains reduce the amount of interference from things that we have already seen, enhancing our perception of novel information.

Huber 研究的一个大脑认知流程叫做“神经习惯化”,这是指对于我们已经经历过的事物,我们的认知处理能力会降低。从神经学角度而言,我们不需要浪费宝贵资源去解析曾经处理过的感官信号。习惯化会帮助我们的大脑减少来自我们已经历事物的干扰,从而提升其对新信息的认知程度。

Habituation is a form of simple memory that suppresses neural activity in response to repeated, neutral stimuli. This process is critical in helping organisms guide attention toward the most salient and novel features in the environment.

习惯化,是一种简单记忆形式,它抑制大脑面对重复发生的刺激物时的神经活动。这一过程在帮助有机体聚焦环境最明显和最新颖特征方面非常关键。

In the same way, if a word is being used to retrieve a certain meaning repeatedly, it’s less energy intensive for your brain to drop the meaning and let the word exist as a sound, as opposed to continually dredging up all of the context and meaning you associate with the word every time you say it. It’s kind of like The Boy Who Cried Wolf, except you're the boy yelling "wolf" repeatedly, and your brain is the town's people who eventually ignore you.

同理,如果一个词被重复用于读取特定含义,那么大脑就会疲于应对,最终让这个词只作为一种声音存在,而不是去每次都孜孜不倦挖掘其背景和含义。这就像是“狼来了”的故事,只是在这里,你是那个不断叫着狼来了的小男孩,你的大脑就是最终忽视你的乡民。

Sensory Overload

感官过载

Huber was part of a study that found support for this idea, where a semantic satiation effect occurred when participants were asked to perform a speed matching task. Participants were given repeated cues of category labels like ‘fruit’, and were asked to name something that belonged to that category like ‘apple’. After a while, participants' responses slowed if the category repeated itself. However, participants’ responses didn’t slow if they were asked to name non-repeated category members like ‘pear’, or if they simply were asked to match the word given to them by the researchers.

Huber 也曾参加过一项佐证了这一理论的研究。在这一研究活动中,当参与者们被要求完成一种快速匹配任务。他们不断被给出重复的类别标签,比如“水果”,并被要求说出一些属于这一类别的物品,比如“苹果”。过了一会儿后,如果这一类别重复,他们的反应就会变慢。但当被要求说出该类别下之前未曾说过的其他物品,比如“梨”,以及当他们只是被要求匹配研究人员给他们提供的词汇时,他们的反应则没有表现出变缓慢。

But associative satiation can happen with all manner of sensory signals. Take for example, this optical illusion, where you are asked to focus on a centre point for a period of time. Lines move in unison towards the centre, drawing you gaze inwards. After a while, a Buddha appears in place of the moving lines and appears to be expanding outwards.

但关联饱和这一现象会发生于所有感官信号上。例如这一视觉错觉。你需要长时间盯着中心点看。所有线条一起向这一中心点移动,向内引导你的目光。片刻后,原来线条的位置出现了一尊佛像,而且看起来仿佛在不断外延。

图片参见:https://michaelbach.de/ot/mot-adapt/index.html

Essentially, the illusion causes your brain to disregard inward motion. When you see the Buddha, it appears as though he is expanding because the brain cells that detect outward motion win the battle against those cells that detect inwards motion (which are now tired). “The advantage here is that by satiating to inward motion, your brain is more ready to perceive outward motion," says Huber. "If there actually was outward motion, that would be something new and interesting and you’d readily perceive it.”

本质而言,这一图片让你的大脑忽略向内的移动动作。当你看到佛像时,仿佛他正在外扩,这是因为负责检测外扩移动动作的大脑细胞打赢了负责检测向内移动动作的大脑细胞(它们现在疲劳了)。“其所占据的优势在于,在对向内移动动作饱和后,你的大脑会做好更充分准备去检测外扩移动动作,”Huber说,“如果的确存在外扩移动动作,那么这对你的大脑就是某种新的和有趣的信号,你就会一下子捕捉到它。”

The next time you experience satiation in one of it’s forms, rather than thinking you are suffering from some sort of brain malfunction, be glad: In a world where we're constantly bombarded with sensory inputs, associative satiation is a technique our minds have developed to filter out what's not important. The world would be a much more confusing place if we didn’t experience it.

下次当你经历某种饱和现象时,不要觉得自己正在遭受某种大脑故障,而是感到庆幸:在一个我们不断被感官输入轰炸的世界,关联饱和是我们大脑为了过滤掉不重要信息而发展出的一种技巧。如果没有这种现象,那么这个世界将远更令人晕头转向。

——《百年孤独》中描述任何人都能闻到 Remedios the Beauty 致命迷人气味但家人因为闻习惯了闻不到的片段。