产后抑郁︱妈妈不必是超人

北师大家庭与儿童发展实验室

我们隶属于北京师范大学发展心理研究院,专注于中国婚姻与家庭研究,致力于将实用有趣的学术成果分享给大家。本期作者

王 淼

北京师范大学心理学部2019级本科生

在近期上演的都市女性情感剧《今生也是第一次》中,女主陈兰青(唐艺昕饰)一直以为生孩子是一件很简单的事,然而在鬼门关走了一遭才生下女儿后,她发现产后的生活也是一地鸡毛:婆婆和妈妈一切都只为孩子考虑,承诺“你只管生就好”的丈夫也无法理解她的感受,陈兰青的饮食、娱乐乃至工作都在很大程度上受到了限制,还要忍着疼痛坚持给孩子喂奶。

最终痛苦达到巅峰的陈兰青爬上了楼顶,嘀咕着“我不要做妈妈”意欲跳楼,还好被丈夫拦下才没有酿成惨剧。

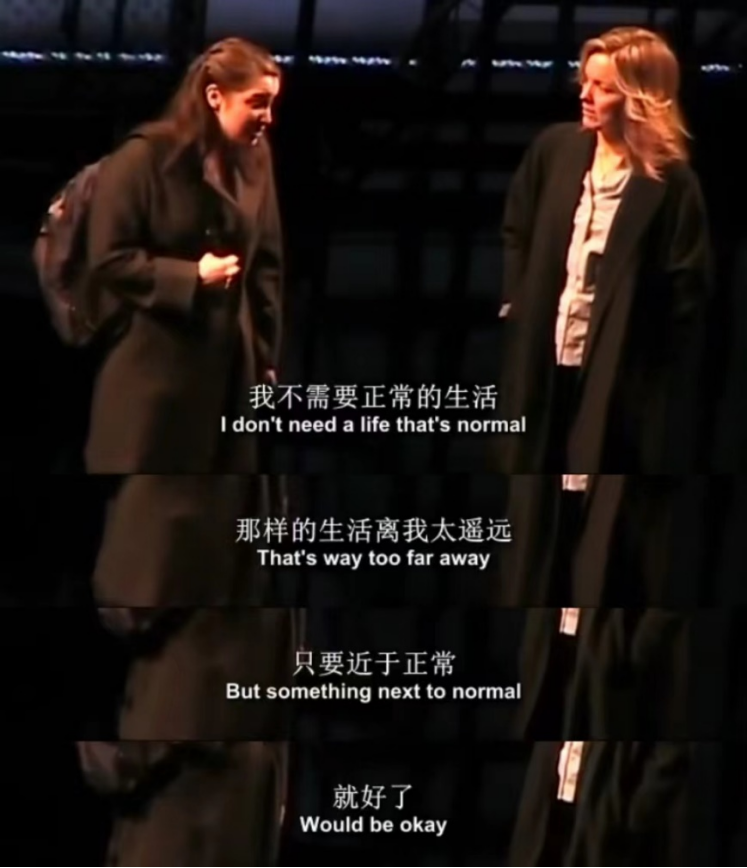

“女本柔弱,为母则刚”,这是对母亲的赞美,也是对母亲的束缚与苛求。生理上的不适已然会使一位母亲筋疲力竭,家人过多的要求和缺乏理解更是雪上加霜。日剧《产科医鸿鸟》中提到:“产后抑郁属于一种精神疾病,却因为带有‘产后’两个字,而被人们看轻了它的严重性。”妈妈并不是超人,我们需要了解、正视、并更科学地看待产后抑郁。

01

了解产后抑郁

产后抑郁

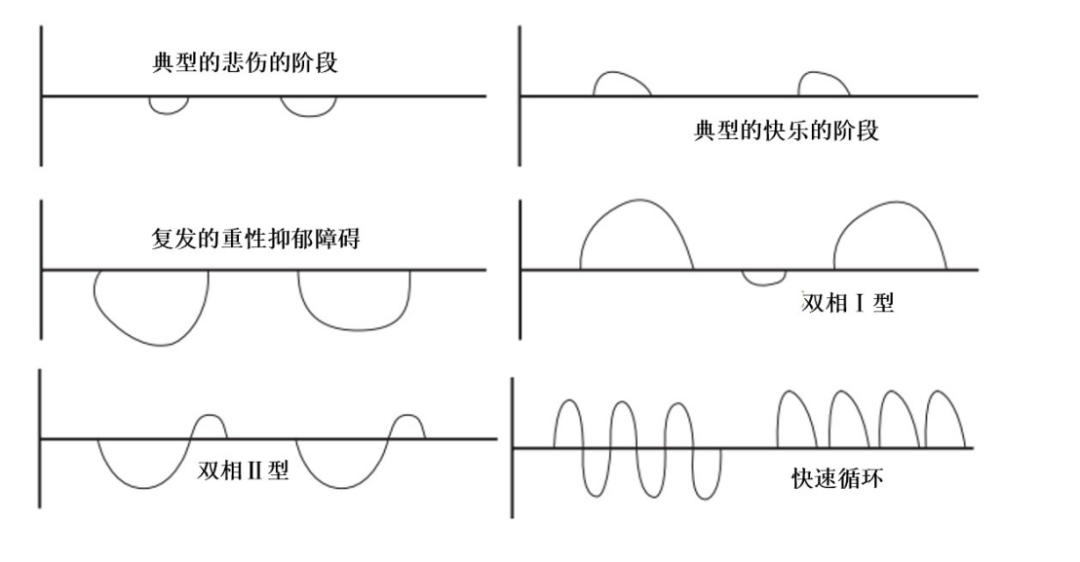

产后抑郁(postpartum depressive, PPD)一般指女性产后出现的抑郁症状,诊断标准与重性抑郁障碍相似,持续时间较长,且会明显地影响生活生理、人际交往、工作学习等功能,具体表现为烦躁、悲伤、沮丧、焦虑、恐惧等负性情绪,同时伴有头晕乏力、失眠、食欲不振等躯体症状,严重者甚至出现幻觉、自杀以及杀婴行为,需要接受治疗,多达10%-15%的产妇会经历这种严重、持久的情绪障碍(汪大彬 等, 2023)。

产后抑郁,从母亲到家庭

产后阶段,再坚强的女性也可能会无缘无故哭泣,再温柔的女性也可能会对不停哭闹的孩子抓狂,她们和家人并不了解或羞于承认产后抑郁,因而不能及时获得帮助与治疗,这让妈妈们承受更多的压力与负面评价,极有可能加重她们的抑郁症状,且得不到及时治疗的产后抑郁患者日后更易复发抑郁(Seyfried & Marcus, 2003)。

值得注意的是,产后抑郁所影响的并不只是母亲,而是整个家庭。

研究发现,产后抑郁患者会花更少的时间进行母乳喂养(Dias & Figueiredo, 2015),且高达60%的产后抑郁患者会控制不住地出现攻击婴儿的想法(Patel et al., 2012)。

其次,患有产后抑郁的母亲会更少回应孩子,对孩子的需求和情绪不敏感,也更多表现出消极情绪。这些行为都会新生儿造成不良影响,如使之身体健康状况更差、易患精神疾病、易形成不安全依恋、人际交往困难等(Burke, 2003)。

此外,在与产后抑郁母亲相处的过程中,父亲及其他亲密照料者也难免受到影响。夫妻关系以及母亲与长辈的关系可能出现前所未有的问题,而焦头烂额的父亲也同样容易患上抑郁(Field, 2010; Rao et al., 2020)。

02

是什么让母亲变得脆弱?

看了上述的这些内容,有些人可能产生这样的疑问:产后抑郁真有这么严重?

事实表明,产后抑郁可能和人们想象的不太一样。首先,产后抑郁的发生比人们想象得更普遍,不必为此自责。其次,产后抑郁的发病原因是复杂的,生理、环境和个人特质等因素都会影响到产妇患产后抑郁的风险。

(1)生理因素

激素水平变化的影响。激素水平的变化是无法避免的,其影响是难以凭主观意志控制的。妊娠期女性体内的雌二醇、孕酮等雌激素浓度显著增加,母体逐渐适应远超常值的雌激素水平,而产后雌激素水平迅速下降到孕前水平,某些对雌激素水平波动敏感的女性会因此出现抑郁症状。

(2)环境因素

缺乏社会支持会大大增加产妇患上产后抑郁症的风险。通俗来说,社会支持是指亲人、朋友等人向受助者提供的物质或精神上的帮助与支持。缺乏社会支持,特别是缺乏来自丈夫的支持,会让女性的育儿与家务负担加重、需求无法及时得到满足、体会到更多的挫败感,从而增加了其患病的风险(Cho et al., 2022; Terada et al., 2021)。

(3)个人特质

研究表明,神经质水平较高的个体情绪较不稳定。高神经质的女性在面临压力时会产生强烈的负面情绪,怀孕和分娩会为其带来压力,并导致她们陷入担忧、沉思和情感回避中,这使得她们更容易出现产后抑郁症状。类似地,脆弱人格(包含焦虑、担忧、敏感、缺乏自信、善变以及轻微的强迫等特质)会通过影响母亲自我效能感而诱发产后抑郁(Han et al., 2022; Puyané et al., 2022)。

除上述因素外,产妇年龄较小、失业、意外怀孕、早产、吸烟、滥用药物等因素也会导致其患产后抑郁风险增加。

03

预防产后抑郁,

我们可以做些什么?

了解了致病风险因素后,我们就有了预防产后抑郁的方向,下文将提出一些建议,希望能够给有小宝贝的家庭提供一些帮助。

(1)留心自身情况,及时进行筛查诊断

女性产后体内激素含量变化较大,情绪和精力容易受到影响,特别是平时对激素变化就比较敏感的人群(如经期及经期前后身体和情绪状态明显比平时差的女性)。妈妈们要关注自己的状态,如果出现产后抑郁相关症状要及时就医进行筛查,确诊则需要按医嘱进行治疗。

(2)适当运动、保持饮食健康,提升孕期身心抵抗力

身体健康是心理健康的基础。研究表明,孕期在专业指导下坚持运动(Lewis et al., 2021),多吃水果、少吃氧化剂含量较高的红肉及其副产品等可以降低患产后抑郁的风险(Flor-Alemany et al., 2022)。健康的饮食、定期的锻炼、良好的睡眠都是抵御产后抑郁与压力的有效力量。

(3)学习育儿知识

妈妈们和家人可以在生产前通过阅读、网络、讲座、宣传栏等多了解科学的育儿知识,必要时可以进行线下或线上的医疗保健咨询,了解如何应对照顾孩子的过程中可能出现的挑战,这样可以增强妈妈抚养孩子的信心,缓解焦虑,也可以使准妈妈们面对这些问题时更加从容。

(4)家人和朋友的支持

分娩意味着离开工作或学校,要应付孩子的需要和问题,忍受身体上的疼痛,没有时间参加社交活动等。因此社会支持,特别是来自家庭成员的支持,对妈妈们来说是一种强有力的帮助。家人和朋友可以多向妈妈们表达关心、理解与爱,一同了解育儿和产后恢复的知识,在产后与其一同分担工作、家务和照顾孩子的责任,多鼓励和安慰她们。

04

已经患上产后抑郁,

怎样帮助母亲好起来?

产后抑郁和非产后抑郁类似,建议通过药物和心理治疗来缓解和治愈,越早接受治疗症状就能够越早得到控制,恢复所需的时间也越短。

(1)药物以及仪器治疗

确诊产后抑郁的妈妈们应遵医嘱坚持服用药物,按时复诊。如有必要,可以考虑接受经颅磁等仪器治疗以及在精神科医院住院治疗。

(2)心理治疗

具有以下特点的心理治疗在应对产后抑郁方面有着显著的效果:

a. 针对母亲自我效能感的治疗(Law et al., 2019)

b. 认知行为疗法、以正念为基础的认知训练、元认知训练等与认知相关的疗法(Bohne et al., 2022)

c. 婚姻/家庭/人际治疗:

家庭新成员的到来会使夫妻对彼此的关心减少,此时妻子的身体与心理都处于较为脆弱的状态,而丈夫需要努力工作来补偿妻子产假期间家庭收入的减少,二者很难为彼此提供支持,且更容易发生冲突,使婚姻满意度降低。此外,妈妈们与婆婆的关系对其心理健康乃至夫妻关系都有重要的影响。

(3)侧重婴儿护理的干预

改善婴儿睡眠质量等针对婴儿及其身体健康的干预能够缓解妈妈们的焦虑,并改善其身体健康状况,从而缓解其抑郁症状(Skodova et al., 2022)。

(4)进行体育锻炼

坚持运动不仅能够预防产后抑郁,还能够减轻已经患病女性的症状(He et al., 2023),但需要在医生等专业人士的指导下进行体育运动。

05

写在最后

妈妈不必是超人,请多给自己一些宽容与关怀,幸福快乐的妈妈能够给宝宝更好的爱。产后抑郁不是洪水猛兽,科学预防,积极就医,全家共同努力,焦虑与悲伤终会云开雾散。感谢每一位伟大的母亲以及默默支持她们的家人。

“我希望你被爱着,我希望你要快乐。”

END

参考文献

Bogdan, I., & Turliuc, M. N. (2022). Intimacy and postpartum depression: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Child and Family Studies.

Bohne, A., Høifødt, R. S., Nordahl, D., Landsem, I. P., Moe, V., Wang, C. E. A., & Pfuhl, G. (2022). The role of early adversity and cognitive vulnerability in postnatal stress and depression. Current Psychology.

Burke, L. (2003). The impact of maternal depression on familial relationships. International Review of Psychiatry, 15(3), 243-255.

Cankaya, S., & Alan Dikmen, H. (2022). The effects of family function, relationship satisfaction, and dyadic adjustment on postpartum depression. Perspectives of Psychiatric Care, 58(4), 2460-2470.

Cho, H., Lee, K., Choi, E., Cho, H. N., Park, B., Suh, M., . . . Choi, K. S. (2022). Association between social support and postpartum depression. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 3128.

Desta, M., Memiah, P., Kassie, B., Ketema, D. B., Amha, H., Getaneh, T., & Sintayehu, M. (2021). Postpartum depression and its association with intimate partner violence and inadequate social support in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 279, 737-748.

Dias, C. C., & Figueiredo, B. (2015). Breastfeeding and depression: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Affective Disorders, 171, 142-154.

Evans, C., Kreppner, J., & Lawrence, P. J. (2022). The association between maternal perinatal mental health and perfectionism: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(4), 1052-1074.

Felder, J. N., Roubinov, D., Zhang, L., Gray, M., & Beck, A. (2023). Endorsement of a single-item measure of sleep disturbance during pregnancy and risk for postpartum depression: A retrospective cohort study. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 26(1), 67-74.

Field, T. (2010). Postpartum depression effects on early interactions, parenting, and safety practices: A review. Infant Behavior & Development, 33(1), 1-6.

Flor-Alemany, M., Migueles, J. H., Alemany-Arrebola, I., Aparicio, V. A., & Baena-Garcia, L. (2022). Exercise, Mediterranean diet adherence or both during pregnancy to prevent postpartum depression-GESTAFIT trial secondary analyses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21).

Flores, D. L., & Hendrick, V. C. (2002). Etiology and treatment of postpartum depression. Current psychiatry reports, 4(6), 461-466.

Han, L., Zhang, J., Yang, J., Yang, X., & Bai, H. (2022). Between personality traits and postpartum depression: The mediated role of maternal self-Efficacy. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, Volume 18, 597-609.

He, L., Soh, K. L., Huang, F., Khaza'ai, H., Geok, S. K., Vorasiha, P., . . . Ma, J. (2023). The impact of physical activity intervention on perinatal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 321, 304-319.

Kirpinar, I., Gozum, S., & Pasinlioglu, T. (2010). Prospective study of postpartum depression in eastern Turkey prevalence, socio-demographic and obstetric correlates, prenatal anxiety and early awareness. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(3-4), 422-431.

Law, K. H., Dimmock, J., Guelfi, K. J., Nguyen, T., Gucciardi, D., & Jackson, B. (2019). Stress, depressive symptoms, and maternal self-efficacy in first-time mothers: Modelling and predicting change across the first six months of motherhood. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 11(1), 126-147.

Lewis, B. A., Schuver, K., Dunsiger, S., Samson, L., Frayeh, A. L., Terrell, C. A., . . . Avery, M. D. (2021). Randomized trial examining the effect of exercise and wellness interventions on preventing postpartum depression and perceived stress. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 21(1).

Low, S. R., Bono, S. A., & Azmi, Z. (2023). Prevalence and factors of postpartum depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: A Review. Current Psychology, 1-18.

Marin-Morales, D., Toro-Molina, S., Penacoba-Puente, C., Losa-Iglesias, M., & Carmona-Monge, F. J. (2018). Relationship between postpartum depression and psychological and biological variables in the Initial postpartum Period. Maternal and Children Health Journal, 22(6), 866-873.

Neely, M. E., Schallert, D. L., Mohammed, S. S., Roberts, R. M., & Chen, Y.-J. (2009). Self-kindness when facing stress: The role of self-compassion, goal regulation, and support in college students’ well-being. Motivation and Emotion, 33(1), 88-97.

Okun, M. L., Mancuso, R. A., Hobel, C. J., Schetter, C. D., & Coussons-Read, M. (2018). Poor sleep quality increases symptoms of depression and anxiety in postpartum women. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 41(5), 703-710.

Patel, M., Bailey, R. K., Jabeen, S., Ali, S., Barker, N. C., & Osiezagha, K. (2012). Postpartum depression: A review. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 23(2), 534-542.

Pedro, L., Branquinho, M., Canavarro, M. C., & Fonseca, A. (2019). Self-criticism, negative automatic thoughts and postpartum depressive symptoms: The buffering effect of self-compassion. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 37(5), 539-553.

Puyané, M., Subirà, S., Torres, A., Roca, A., Garcia-Esteve, L., & Gelabert, E. (2022). Personality traits as a risk factor for postpartum depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 298, 577-589.

Qi, W., Liu, Y., Lv, H., Ge, J., Meng, Y., Zhao, N., . . . Hu, J. (2022). Effects of family relationship and social support on the mental health of Chinese postpartum women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 22(1), 65.

Rao, W.-W., Zhu, X.-M., Zong, Q.-Q., Zhang, Q., Hall, B. J., Ungvari, G. S., & Xiang, Y.-T. (2020). Prevalence of prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers: A comprehensive meta-analysis of observational surveys. Journal of Affective Disorders, 263, 491-499.

Séjourné, N., Alba, J., Onorrus, M., Goutaudier, N., & Chabrol, H. (2011). Intergenerational transmission of postpartum depression. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 29(2), 115-124.

Seyfried, L. S., & Marcus, S. M. (2003). Postpartum mood disorders. International Review of Psychiatry, 15(3), 231-242.

Skodova, Z., Kelcikova, S., Maskalova, E., & Mazuchova, L. (2022). Infant sleep and temperament characteristics in association with maternal postpartum depression. Midwifery, 105, 103232.

Tauqeer, F., Ceulemans, M., Gerbier, E., Passier, A., Oliver, A., Foulon, V., . . . Nordeng, H. (2023). Mental health of pregnant and postpartum women during the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: A European cross-sectional study. BMJ Open, 13(1), e063391.

Terada, S., Kinjo, K., & Fukuda, Y. (2021). The relationship between postpartum depression and social support during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research, 47(10), 3524-3531.

Thompson, K. D., & Bendell, D. (2013). Depressive cognitions, maternal attitudes and postnatal depression. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 32(1), 70-82.

Tsuno, K., Okawa, S., Matsushima, M., Nishi, D., Arakawa, Y., & Tabuchi, T. (2022). The effect of social restrictions, loss of social support, and loss of maternal autonomy on postpartum depression in 1 to 12-months postpartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders, 307, 206-214.

Van der Zee-van den Berg, A. I., Boere-Boonekamp, M. M., Groothuis-Oudshoorn, C. G. M., & Reijneveld, S. A. (2021). Postpartum depression and anxiety: A community-based study on risk factors before, during and after pregnancy. Journal of Affective Disorders, 286, 158-165.

Zheng, J., Sun, K., Aili, S., Yang, X., & Gao, L. (2022). Predictors of postpartum depression among Chinese mothers and fathers in the early postnatal period: A cross-sectional study. Midwifery, 105, 103233.

耿希文, 成昕昕, 李自发, 郭淼, & 魏盛. (2022). 产后抑郁症的神经生物学机制. 生理科学进展, 53(5), 5.

汪大彬, 阎文军, 王玲凯, 胡琼花, 朱磊 & 何栋刚. (2023). 超声引导下右侧星状神经节阻滞对初产妇剖宫产术后睡眠质量和产后抑郁的影响. 卫生职业教育(04),147-150.

策划 | 蔺秀云

撰稿 | 王 淼

编辑 | 丁欣怡

排版 | 丁欣怡

图源网络 | 侵删