Savior/Messiah Complex/救世主情结

While lending others a helping hand is typically a good thing, for those with savior complex, it becomes an unhealthy means of coping or validation.

尽管向他人伸出援手通常是好事,但对于患有救世主情结的人而言,这种行为通常是一种不健康的应对机制或寻求认可的方式。

Savior complex occurs when individuals feel good about themselves only when helping someone, believe their job or purpose is to help those around them, and sacrifice their own interests and well-being in the effort to aid another.

救世主情结是指:一个人只有在帮助别人时才会自我感觉良好,并认为他们的使命就是帮助周围的人,而且会牺牲自身利益和幸福去试图帮助他人。

Although this knight in shining armor, straight-out-of-a-fairy-tale behavior might sound too good to be true, it’s an unhealthy coping mechanism that can do more harm than good.

尽管这种身着闪亮铠甲,宛若童话般的骑士听起来可能美好得不大可能,但实际上这是一种弊大于利的不健康应对机制。

People with savior complex try to feel in control by fixing the lives of others — often in order to distract themselves from their own anxiety or powerlessness. Helping others also induces a sense of validation in such people, helping them feel better about their own lives — resulting in an obsessive need to fix in order to maintain this good feeling.

救世主情结者通过挽救别人人生的方式来试图寻找到控制感,他们这种行为通常是为了将自己的注意力从自身的焦虑和无助感上转移开。帮助他人同时也会给助人者带来一种认可感,让他们对自己人生的自我感觉更好,这就导致他们为了维持这种良好的自我感觉,而陷入一种“想要救助他人”的偏执需求中。

If you’re genuinely trying to help others, you may want to pay attention to overdoing it. Even the kindest actions can be harmful to mental and physical health. If you’re helping because you feel superior or are craving power, or if your actions harm others, it can be a sign to get help. In some cases, a person with a messiah complex may treat others poorly and demand obedience. Some people with a savior complex have messianic delusions and actually think they are a savior as taught in the Bible.

如果你真心想要帮助他人,那么应注意不要过火。即使最善义的行为也可能会对精神和生理健康有害。如果你是因为想要优越感或渴望权力而帮助他人,或者你的行为伤害到了他人,那么这些都是你需要寻求帮助的征兆。有时,救世主情结者可能会恶劣对待他人,并要求别人顺从自己。一些救世主情结者甚至还会产生错觉,真的觉得就是圣经中所说的真正救世主。

If your good intentions go off the rails -- whether you mean for them to or not -- that’s known as pathological altruism. It can be a result of having a savior complex.

Predispositions to the savior complex can sometimes be traced back to dysfunctional family dynamics in childhood — resulting in the unhealthy coping mechanism that continues into adulthood.

如果你的善意并未善终,无论这是否是你本意,这种情况被称为“病理性利他主义”。这就可能是救世主情结的后果之一。一些人易产生救世主情结,其原因有时可能追溯到童年时期功能失调(不正常)的家庭关系,这类家庭关系导致了延续至成年期的不健康应对机制。

People with savior complex often believe they are somehow better than others because they help people all the time, leading to feelings of being morally superior. In addition, experts note that savior complex can induce feelings of omnipotence, making people who experience it prone to believing no one else can save others they way they can.

救世主情结者通常认为他们在某种意义上要优于别人,因为他们总是在帮助他人,因此他们产生一种道德优越感。另外,专家还提出,救世主情结会催生一种无所不能感,让患者易于认为在救助他人方面,自己无人能敌。

One of the most famous examples of a dangerous leader with a savior complex was Adolf Hitler. He viewed himself as the savior of the entire nation of Germany, and believed that it was his responsibility to save them from the scourge of undesirable people attempting to challenge German dominance. Tragically, much of Germany fell in line behind this self-declared savior, and the horrors of World War II and the Holocaust followed.

患有救世主情结的危险领导者的最著名例子之一,就是希特勒。他将自己视为整个德国的救世主,并认为挽救德国,使德国免遭试图挑战德国人主导地位的不良种族的祸害。悲惨的是,德国大部分地区都选择了追随这一自封的救世主,接踵而至的,便是恐怖的二次大战和种族屠杀。

Because people with savior complex tend to “seek people who desperately need help and to assist them, often sacrificing their own needs,” they are often “identified as ‘nice guys,’ but the truth is emotionally healthy [people] will never have a compelling need to seek that kind of validation. That itself should be an alerting sign,” notes Sara Benson, PsyD, a psychologist.

因为患有救世主情结之人常常会“搜寻迫切需要帮助之人,并向他们提供帮助,而且通常会牺牲个人需求,“他们通常会被视为“好人”。但事实上,情绪健康人群从来都不会具有寻求这种认可的强迫型需求。这种对认可的强迫需求本身就应该是一个警报信号。心理学家与心理学博士Sara Benson表示。

These personality characteristics are often driven by a sense of nobility, that such selfless behavior is the “right thing to do”. This can gradually evolve into feelings of superiority towards those they are helping, and the line between being generous and being patronizing becomes blurred. Becoming overly emotionally or financially invested in “tragic cases” can result in a pattern, a dangerous cycle where temporary improvements are seen as “victories”, but the individuals receiving help fail to develop their own tools for self-help and self-motivation.

这些性格特点的驱动因素通常是一种高尚感,即,感到这种无私行为是“正确的事”。这会逐渐演变为对受助者的优越感,而且慷慨与施舍之间的界限会逐渐变得模糊。从情感或经济上过度投入于这些“悲惨人物”会导致一种行为模式、一种危险的循环,即,短暂的改善被视为“胜利”,但受助者却未能培养出自助、自我驱动的工具。

Behavioral experts agree that “helping” does indeed have the potential to become an addiction. When we help others, our brains emit three chemicals, often referred to as the happiness trifecta:

行为专家也认为帮助他人的确会可能具有成瘾性。当我们帮助他人时,我们大脑会释放三种化学物质,它们通常被称为幸福三宝。

Serotonin (produces intense feelings of wellbeing)

血清素(产生强烈幸福感)

Dopamine (intensifies motivation)

多巴胺(强化自驱性)

Oxytocin (increases a sense of connection to others)

催产素(提升与他人的连接感)

The “feel good” outcome of this combination naturally makes us want to repeat it. But when our need to help becomes so insatiable that our sense of purpose is tied directly to others, specifically, them needing our guidance, it is no longer other people that we are helping. It is ourselves.

这一组合的良好感觉效果自然而然就会让我们想要再来一次。但当我们想要帮助他人的需求变得是如此难以被满足,以至于我们的目标感与他人直接捆绑在一起,具体而言,与别人对我们指导的需求而绑定在一起,那么我们帮助的就不再是别人,而是自己。

Psychologists refer to this particular problem as agency addiction. It is defined as a need to rescue others through helping — with our advice, coaching, or ideas — in order to bolster our feelings of self-importance. Whereas those with a healthy sense of agency are just as gratified by helping others succeed as they are seeing them succeed on their own.

心理学家将这种特定问题称为主观能动性成瘾症。其定义是,需要通过帮助他人(以提建议、指导或想法的形式等)来拯救他人,目的是为了提振我们的自我重要感。而拥有健康主观能动性的人无论是帮助别人成功,或者看到别人自己获得成功,所获得的满足感都是一样的。

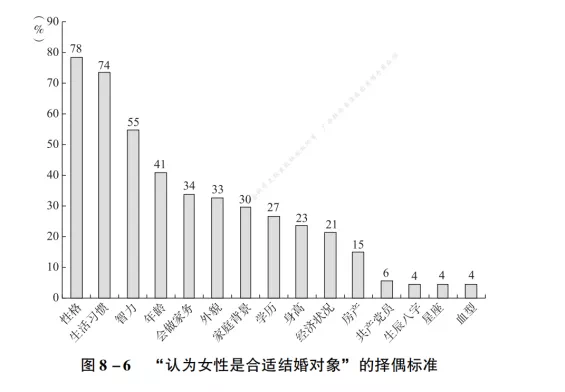

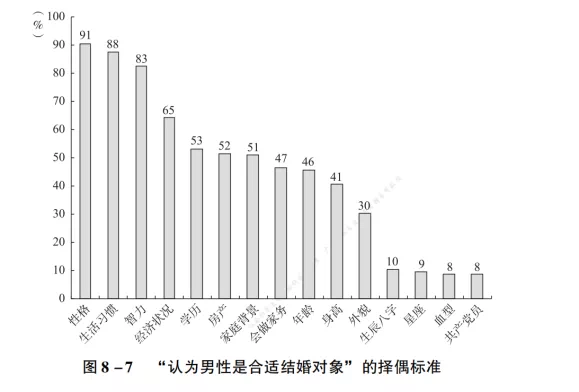

This problem often arises in personal relationships, in which a person perpetually seeks out those who “need” help, such as those struggling with addiction, poverty, or mental health troubles. This desire to “fix” or “change” someone who has a perceived problem can turn them into a project or a patient, rather than a lover or partner. It has also been observed that white teachers who work in challenging environments, often in communities of color, develop certain biases, beliefs and patterns of behavior that are aligned with a savior complex.

这一问题通常发生于个人感情关系中,即,一个人总是会去寻找那些“需要帮助”的对象,比如挣扎于瘾症、贫穷或精神健康问题中的人。因为他们“想要“修复”或“改变”某个在他们看来有问题的人,这种念头就将受助者转变为了一个项目,或一位病人,而非爱人或伴侣。另外根据观察,一些在具有挑战性的环境中,通常是在有色人群社群中工作的白人教师,往往会产生一些与救世主情结相符合的特定偏见、理念和行为模式。

While helping people out generally isn’t harmful, an individual with savior complex can actually harm more than they help, by trying to fix something they don’t have the skills to fix, rather than entrusting the job to someone who does. “If your partner has a drug or alcohol problem and you refuse to leave them because they ‘need’ you — this is also enabling behavior. They have a serious health problem that your presence alone cannot fix,” Julie Williamson, a counselor, notes as an example.

尽管整体而言帮助他人并非有害,但一位患有救世主情结的人可能实际上造成的伤害要大于帮助,因为他们会试图去修复一些他们并无能力修复的问题,而非选择让具有相应能力的人来做这件事。“如果你的伴侣有吸毒或酗酒问题,而且你拒绝离开他们,因为他们“需要”你,那么这也是一种纵容行为。他们具有严重健康问题,只是你陪在他们身边,并无法解决这一问题,”心理咨询师 Julie Williamson举例说。

Savior complex behavior can also hinder the growth of the individual being aided and constant attempts to fix their lives and can lead to codependency, they neither learn to take responsibility for their own actions nor develop independent, internal motivation.

救世主情结还会阻碍受助者的成长,而且持续试图修复他们的人生,会导致二人之间产生病态共同依赖。受助者既不会学会为自己的行为负责,也无法培养出独立、内在的自驱性。

Because of these effects, savior complex can, in fact, add an unhealthy and often toxic dynamic to romantic relationships, as the individual with savior complex treats the relationship more like a parent-child or teacher-student relationship in a constant endeavor to fix their adult partners. Being “made to feel as if [they aren’t liked] as they are” and need fixing can make the partner frustrated and resentful, Maury Joseph, PsyD, a psychologist, explains.

因为这些后果,救世主情结实际上会为感情关系带来一种不健康且通常有害的关系模式:救世主情结者因为试图不断“修复”伴侣,对待这段感情更像是将其视为亲子或师生关系。他们让伴侣感觉自身不那么受人喜欢,而且自身有问题需要修复,这会让伴侣感到沮丧并愤懑。心理学家和心理学博士 maury Joseph表示。

“Relationships are supposed to be mutually enjoyable and give-take, not charity cases. … You should enter into relationships because you share common values and have a connection. If you are entering a committed relationship with the goal of changing your partner then [they’re a] project, not a partner,” David Bennett, a counselor, explains.

“感情关系应该是带给彼此愉悦,彼此付出的,而不是慈善事业……你进入一段感情的原因应该是你们拥有相同的价值观,并心意相通。如果你进入一段固定恋情的目标是改变对方,那么,对方不过是你的一个项目而已,并非伴侣。”心理咨询师David Bennett说到。

The savior complex harms the fixer as well as their people-projects. Constant helping and sacrificing for others can cause them to feel they are taken for granted when those around them get used to their helpfulness. It can also cause them to experience burnout due to the amount of energy they expend in trying to help others. “Saviors might see symptoms similar to those in people taking care of ailing family members. … They might feel fatigued, drained, depleted in various ways,” Joseph adds.

救世主情结者同时也对救助者有害。不断帮助他人、为他人牺牲,会让他们觉得当身边的人习惯了他们的帮助后,就把这些帮助视为了理所当然。而且这种情结也可能会导致他们身心俱疲,因为他们总是花费大量精力试图去帮助别人。“救世主情结者身上往往会表现出与那些照顾患病家属之人相类似的症状……他们可能会从各种方面感到疲倦、感觉自己被抽干、被掏空”Joseph补充说。

How Can a Savior Complex Harm Me?

救世主情结对我有何害处?

Even if you truly want to help others (that’s called altruism), feeling like you have to help others can:

即使你是发自真心地想要帮助他人(这被称为利他主义),如果你感觉你不得不去帮助别人,那么这可能会:

Put you in danger physically if you try to save someone in a dangerous situation

Affect your mental state, especially if you aren’t able to save the other person

Cause you to neglect your own physical needs, which could lead to illness

Lead you to get burned out

Affect your personal relationships

Negatively affect the person or people you’re trying to help

如果你试图去救一个处于危险情形中的人,可能会给你带来生命危险;

影响你的精神状态,尤其是如果你无法成功救助对方;

导致你忽视个人生理健康需求,这可能会导致疾病;

让你身心俱疲;

影响你的个人感情关系;

对你试图救助的人产生负面影响。

Is a Savior Complex a Mental Disorder?

救助者情结是否是一种精神障碍?

No, but people with mental disorders may get a messiah complex. It’s compared to grandiosity, or grandiose ideas about themselves. That’s when someone has an exaggerated sense of their importance, power, or identity. It’s common in people with bipolar disorder. The messiah complex has also been linked to schizophrenia and delusional disorder.

不。但患有精神障碍者可能会产生救助者情结。这类似于一种自大感,自命不凡感,即对自身重要性、权力或身份有着夸大的错误认知。这在边缘人格障碍中常见。救助者情结还被认为与精神分裂症和妄想障碍相关联。

You don’t have to have a mental disorder to experience a savior complex. You may start helping others with good intentions and continue that way, or develop a messiah complex over time. Some people help others at their own expense because they want to feel good about themselves or they want to feel like they’re in control of others. Just because you experience a savior complex doesn’t mean that it goes on to hurt others, but it can be harmful to your general health or theirs.

你并不一定非得有某种精神障碍才会发展出救世主情结。一开始你帮助别人时,可能是本着善意,但随着时间推移就萌生了这种情结。一些人会舍己助人,因为他们想要那种良好的自我感觉,或者想要感到自己掌控对方。只是因为你有救世主情结,并不意味着它就一定会伤害他人,但它却可能会对你的或他们的整体健康有害。

What Are the Symptoms of a Savior Complex?

救世主情结的症状

You may have a messiah complex if you:

如果你有以下症状,那么你就可能具有救世主情结:

1) Want to help other people.

想要帮助他人。

2) Want better self-esteem or self-worth.

想要更高的自尊感或自我价值感;

3) People with megalomania can set out to help people (and have a messiah complex), too.

患有夸大妄想的人也可能会试图去帮助他人(并具有救世主情结);

4) Have codependency. If you feel responsible for another person’s needs -- and enable them to fill those needs, even if they’re negative -- you may be more prone to experience a messiah complex or pathological altruism.

病态共同依赖。如果你觉得自己应该对某个人的需求负责,并纵容他们满足他们的这些需求,即使这些是不健康的需求,那么你就更易于产生救世主情结或病理性利他主义。

5) Have an eating disorder. People with eating disorders often want to help others instead of themselves. Some experts believe that people with eating disorders may be more likely to have pathological altruism, which is linked to having a messiah complex.

患有饮食障碍。饮食障碍者通常会想要帮助别人,而非自己。一些专家认为,饮食障碍者更易于产生病理性利他主义理念,这种理念则与患有救世主情结相关。

6) Hoard animals. If you have a lot of animals and cannot fully care for them, you are not be doing what’s in their best interest. Some experts associate people who hoard animals with pathologic altruism.

囤积动物:如果你养了很多动物,但却又无法充分照顾它们,那么你的所作所为就并不符合它们的最佳利益。一些专家认为囤积动物者与病理性利他主义之间存在关联。

7) Think you know what’s better for others.

认为你知道什么才对别人更有利。

8) Crave power over others or self-worth. You may start out genuinely wanting to help others and find that you crave the power that it gives you. Then you may stop wanting to help others but only do it for the power or feelings of self-worth.

渴望对他人的权力或渴望自我价值。一开始你可能发自真心想要帮助他人,但却发现你渴望这种助人行为带给你的力量感。之后你再帮助别人时可能就并非出于帮助之心,而只是为了追求这种力量感和自我价值感。

9) Feel superior to others based on race. Beliefs on race can be a driver for a person to feel obligated to help others, too. This is known as white savior complex.

种族优越感。对种族的观念可能也会让你一个人感觉自己有义务帮助别人。这也被称为白色救世主情结。

10) Have delusional disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or other mental disorder.

患有妄想障碍、边缘人格障碍、精神分裂症和其他精神障碍等。

These 17 signs show you may have savior complex in your relationship

感情中你可能患有救世主情结的17个迹象

1) You really want to change and “fix” some fundamental things about your partner

你真心想改变或“修复”对方的一些本质性问题;

2) You feel like you know what’s best for your partner – even more than they do for themselves

你感觉你知道什么才是对对方最好的——甚至比对方自身都要清楚;

3) You treat them like you’re interviewing them or “checking up” on them frequently

你对对方的对待方式经常如同审问或检查;

4) You have many ideas and answers for their life and long-term improvements

对于对方的人生和长期提升,你有很多的想法和答案;

5) You trust yourself more than any professional or expert to help address their problems

在帮助解决对方问题方面,你更信任自己,而非任何专业人士或专家。

6) You start paying their financial costs

你开始承担对方的经济开销;

7) You run your partner’s schedule and organize their life more than they do

在对方的日常计划执行和对方的生活安排方面,你做的要比对方做的多。

8) You’re working overtime while they sink deeper

你越来越马不停蹄劳作,但对方越陷越深(你一直在干活,比如各种家务,对方一直心安理得享受)

9) Your romantic spark is eclipsed by a therapist-patient dynamic

你们的爱情火花被一种心理咨询师——患者的关系模式给遮蔽了。

10) You look after your partner so much you don’t leave enough time for yourself

你如此劳神费力照顾对方,以至于没有足够时间留给自己;

11) You blame yourself for their problems and setbacks

你将对方的问题和挫折归咎于自己;

12) You place your own happiness completely in your ability to help your partner

你将个人幸福完全置于自己帮助对方的能力上;

13) You’re certain that without you your partner would be toast

你坚信如果没有你,对方就完了;

14) You stay in the relationship even if you’re unhappy because you feel a sense of responsibility and dependence

你选择继续这段感情,即使你并不开心,因为你看到一种责任感和依赖感;

15) You don’t think you deserve someone who treats you better

你觉得你配不上一个对你更好的人;

16) Your sex life and emotional bond frays but you just try even harder to help

你的性生活和情感纽带受挫,但你只是更努力地尝试去帮助对方(觉得自己做的还不够多,应该更努力一些,更多沟通一些,满足对方的更多需求)。

17) You feel bound by an invisible cord that just gets stronger with time

你觉得自己被一根隐形的绳子束缚住了,而且这根绳子随着时间推移变得越来越结实;

When you’re in a codependent cycle, it’s not healthy or wonderful.

It drags you and your partner both down, and the wound-mate bond just gets stronger over time.

You feel this overwhelming guilt that you can’t leave them. It’s too late now after all this time.

You feel a wound inside yourself that can only be validated and healed by fixing or rescuing this other individual you care about.

But it’s not true. And it’s time to step out into the sunlight.

当你处于一段病态共同依赖的循环中时,这(种捆绑感)既不健康也并非好事。

它会将你们二人向下越拽越深,这种基于创伤而形成的纽带会随着时间推移逐渐加固;

你感到一种排山倒海般的内疚感,你告诉自己不能离开对方。现在,过了那么久,已经太迟了。

你感到内心有一处伤口,而且只有通过“修复”或拯救你所在乎的另一个人,才能让这一伤口得到认可和愈合。

但这一切并非事实。而且,是时候走出阴霾,沐浴阳光之下了。

You are worthy of love and a strong relationship and you are not compelled or even capable of fixing someone else. It’s OK to recognize and fully accept that and love yourself and love your partner outside the framework of the savior complex. Sometimes there are issues you can work through, sometimes it is time to go your separate ways.

你值得爱,值得一段牢固的感情,你没有义务,甚至也没有能力去修复别人。承认并完全接受这一点,同时在救世主情结框架外爱你自己和爱对方,这完全是可行的。有时有的问题你们可以解决,但有时候则是时候分道扬镳。

Either way: be strong in the deep inner knowledge that you both deserve love that is unshackled and true.

无论如何:坚信你们都值得拥有不被束缚、真正的爱。

So what are solutions for avoiding the “savior” trap with relationships and clients?

如何避免感情关系中和与患者之间的“救世主”陷阱呢?

Process emotions with friends, family and/or other staff members.

与朋友、家人和/或其他同事处理你的情绪;

Set boundaries with other individuals that allow you to balance caring for them with trying to “save” them.

与其他人之间设立界限,让自己能够在照顾它们和挽救它们之间达成平衡;

Say “maybe” or “no” before saying yes in order to give yourself time to weigh options.

在答应之前,说“可能”或“不”,从而给自己时间权衡各种选项;

Slow down enough to be mindful of choices.

足够慢下来,清楚意识到各种选项;

Reach out for support from a therapist or coach in order to receive an objective assessment of your interpersonal issue.

向心理咨询师或导师寻求帮助,从而对自身人际问题获得一份客观评估。

Let your loved one, friend and/or client take responsibility for their actions.

让自己所爱之人、朋友和/或患者为自己的行为负责;

Do not work harder than your friend, loved one and/or client.

在他们自身问题上,不要比你的朋友、所爱之人和/或客户更努力;

Do the best that you can do to support the individual and then “let go” of the results.

尽己所能支持对方,然后不要纠结于结果如何。

Redefining “helping” and “caring.”

重新定义“帮助”和“关心”。

What does “helping” mean to you and for this individual?

“帮助”对你和对方而言意味着什么?

Asking questions

询问

Backing off

不干预

Simply listening

倾听

Offering action steps and coping skills instead of doing the work for them

为对方提供行动步骤和应对技巧,而非为对方代劳;

Ask yourself:

问自己:

Am I helping this person by avoiding natural consequences?

让对方避免承受自然后果,这种行为是否真的是在帮助对方?

Is this decision made to keep them “happy” or for their overall health?

这一决定是为了取悦对方,还是为了对方整体健康情况着想?

Is my action helping them to get better or me to feel better?

我的行为是在帮助他们变得更好,还是为了让我自我感觉更好?

Am I being invited to help?

我有被邀请提供帮助吗?

Do I “want” to or have to do this?

我想要这样做吗?我必须得这样做吗?